Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center patient and research collaborator Erik Sorto, 41 years old, was among the individuals featured in the PBS Series “Searching: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science.”

Sorto, who grew up Boyle Heights, is a C4 quadriplegic, a former gang member, and participated in a procedure at Rancho Los Amigos that implanted electrodes into his brain to help research that might restore mobility to others paralyzed by injury.

Years after becoming paralyzed after a gang shootout, Sorto had implants that enabled him to move a robotic arm using his thoughts. Although the implants were removed after nearly six years of research, due to corrosion, Sorto remains a collaborator in the project.

The technological advancements caused PBS journalists to ask, “What does it mean to be ‘human’ in the age of technology?”

Sorto said he “wasn’t a very good person, when I was able bodied,” but decided to prove that he has become a better person and “is not his past (as a gang member).”

(Photo Courtesy of PBS)

The project was the chance of a lifetime, Sorto said, even though participating in it would mean risking his brain.

His mother, who cares for him daily and his children felt differently. Sorto’s brain was the only part of his body that was still functioning properly, so they asked, why risk it? They were unsure of the advantages of allowing surgeons literally into his skull.

Sorto ultimately decided to participate in the project and said it was emotionally “amazing” to move the robotic arm with his mind. “It was an out-of-body experience and I remembered how much joy I had in my life when I moved that arm.” The robotic arm enabled Sorto to grab a bottle of water, place a straw in the bottle, and bring it to his face to drink.

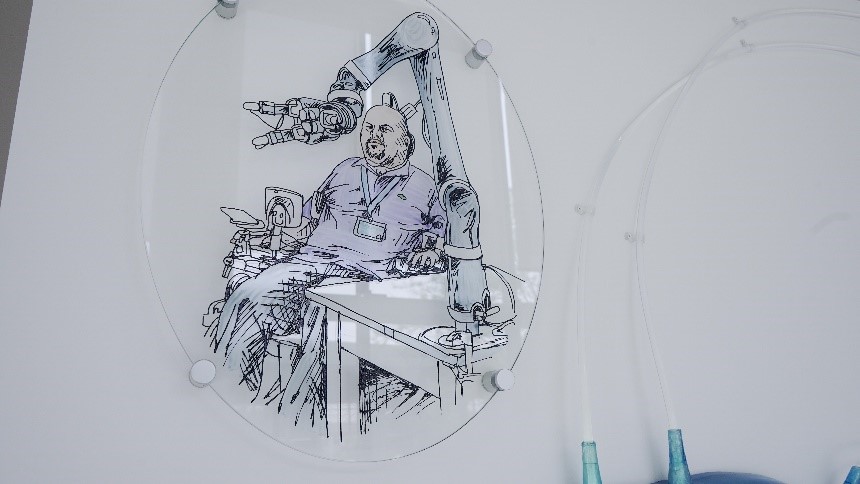

Rancho Los Amigos patient Erik Sorto, who is a quadriplegic, successfully manipulating a robot arm to bring a drink to his face. (Courtesy of PBS)

Most people rarely think about this process, but it takes considerable effort to manipulate an arm to precisely to extend, grab, hold without breaking, and move a beverage container to a new and specific location.

Sorto said he and his doctors joked about him being a cyborg, because he was part human and part robot. But Sorto said that he always felt human during the entire experience.

“Being human,” Sorto said, “is to take what you have, move forward, and within that path, gain the tools to make your situation even better.”

Sorto said his injury also gave him a purpose in life. “Before my injury, I was just trying to survive, just trying to breathe.”

After the procedure, Sorto said his purpose is to help someone else become more physically independent than he will ever be.

Melding Science, Technology and Humans

Dr. Charles Y. Liu of Rancho Los Amigos said in the PBS series that he has “always (been) frustrated with the idea that we can’t fix neurological diseases or injury.” Doctors can fix some issues, but patients must live with any remaining physical challenges.

But the research being conducted at Rancho Los Amigos could overcome many of those challenges. It’s an ongoing research collaboration involving the University of Southern California, the California Institute of Technology, and Rancho Los Amigos to develop brain-controlled prosthetic devices such as robotic limbs to enable injury-caused paralyzed individuals to become more functionally independent.

Liu, a professor and Chair, Department of Neurosurgery and Orthopedic Surgery and Chief of Innovation and Research at Rancho Los Amigos, leads the research collaboration, which began in 2011, with Prof. Richard Andersen of CalTech.

The project with Sorto helped researchers study a new brain area that revealed direct brain-to-machine control and could provide new technological developments to restore independence in people with severe neurological injuries.

Rancho Los Amigos, USC, and CalTech worked collaboratively to obtain Sorto’s brain functions, develop the electrodes, and to safely implant them into his brain.

When bringing a new technology into humans’ bodies, said Christi Heck, a neurologist at USC’s Keck School of Medicine, “you need the scientists (at CalTech) and the clinicians who have the experience working with humans.”

Heck said, “You’re taking really good science (and technology in the form of computer chips, electrodes, and arrays) and bringing it into humans in a very safe way.”

After CalTech researchers mapped Sorto’s brain to identify sections that managed limb movement, sensory perception, and intention (such as “I would like to grab that bottle of water), surgeons needed five hours to apply the implants to the proper locations on Sorto’s brain.

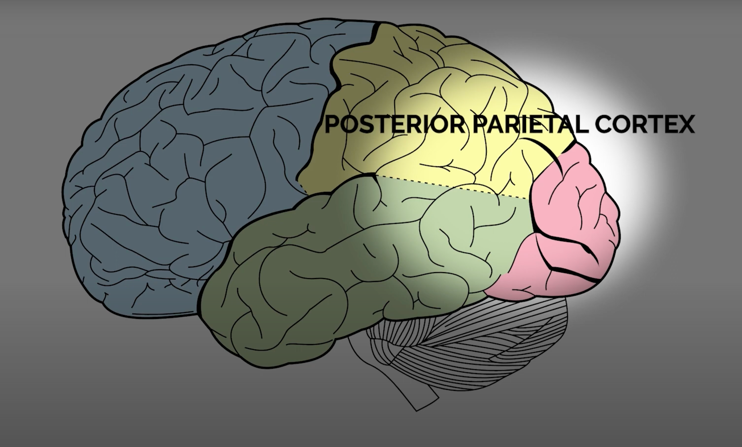

The Rancho Los Amigos collaborators implanted electrodes, in the highlighted area pictured above, to study whether a person’s brain can manipulate a robot arm. (Image Courtesy of PBS)

After the surgery, and physical therapy, Researchers connected Sorto and his electrodes to computer sensors and asked him to think about performing actions with his arms – punching, scratching his head, grabbing things, etc. The computers captured the signals from Sorto’s brain during those thoughts, then researchers developed algorithms to convert those thoughts into instructions for a robot arm.

Because Sorto’s surgery was the first one performed on the posterior parietal cortex, the rear and top section of the brain, everything about the surgery was different, Liu said.

“It’s a little challenging because (Sorto is) a high-spinal cord injured patient and is a little more fragile than our typical patient,” Dr. Liu said.

It’s difficult to position the patient, the needed surgical systems, and the technology that will be implanted into the patient.

Next Stage Research at Rancho Los Amigos

In 2013, researchers implanted two chips into Sorto’s brain, and he came to Rancho Los Amigos daily for more than five years to help researchers develop decoding algorithms to his thoughts. The results of the work were published in Science in 2015 and received international attention. This became one of the most highly visible scientific achievements in this arena at the time.

In 2018, the chips finally stopped functioning, and Sorto underwent surgery to remove them. However, he remains very engaged with the work and is the “face of the project” at Rancho Los Amigos and beyond. His contributions have led to the creation of Rancho Los Amigos’ new “Research and Innovations” program at the newly remodeled Harriman Building, where Sorto’s likeness is featured in the art on the walls.

(Marco Garcia/DHS)

Two additional Rancho patients have since undergone surgery to implant more advanced chips than Sorto’s.

Sorto’s contribution provided the basic science needed to implant six electrode arrays across another patient’s entire motor-sensory system. Sorto, in comparison, had two arrays implanted solely in his brain.

The additional arrays could further improve scientific understanding of the brain that could, eventually, restore movement to patients’ arms after complete injury to the spinal cords.

Every participant in a research project helps to reveal basic science about the brain, and that further perfects technologies that can overcome neurological issues in more patients, Prof. Anderson said.

Sorto – Former Gangster, Father of a Police Officer

Sorto attempted to explain the consequences of his former life by publishing the book, Payback: The Cost of Being a Gangster, in 2007. The book provides graphic descriptions of Sorto’s life as a gangster and the changes he had to manage after becoming paralyzed.

“I wrote the book to make sure that children who read it,” Sorto said with emotional difficulty, “that they wouldn’t follow in my footsteps.”

He hopes that his book will connect with children growing up in Boyle Heights and East Los Angeles and prompt them to make better daily decisions in life. Hopefully, “they will see the consequences of living that kind of lifestyle,” Sorto said.

Some people living in Boyle Heights don’t think about medicine, science, or clinical research, Sorto said. “You think about not getting killed. You think about surviving, staying safe, not getting (beaten up), or shot. You have to know where you are (in the neighborhood), so you won’t get killed.”

Sorto never thought that would be alive at the age of 41. “I thought that I would be dead by 20.”

Sorto has two children, a son who is a police officer and a daughter who is studying biomedical engineering, as well as a granddaughter.

“I’m very proud of my son,” Sorto said, adding that his daughter may “pursue a career in spinal cord injury.”

Sorto never thought that, in his condition, that we would have such thoughtful children. “But I hope that my injury helped them become the people they are now.”

Other Benefits of the Research Project

CalTech Prof. Anderson said the recovery process and participation in the research had great therapeutic benefits for Sorto. “It gives him a way to get out of the house. He has a job. He goes to work, he’s paid for the trials, he’s interacting with a lot of people. So, it provides a really rich and exciting environment for him.”

Sorto said, “I was just happy to be part of such a beautiful project. It’s probably one of the best things that has happened to me in my life.”

Sorto said the project gave him a purpose in life. “As much as the project needed someone in my condition, I needed it in my life. I loved it (being in the project).”

He also learned a valuable lesson: “Anything’s possible if you really put your brain to it.”

Sorto said he would willingly have the implants again. “I asked Dr. Liu to reimplant me. I would have loved it. But I needed FDA approval,” Sorto said.

He also has a special message for Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, which has a picture of Sorto among the great medical and scientific achievements in medicine and brain surgery. “It’s a great honor (to be pictured here.) It’s Rancho Los Amigos, the hospital that sparked me to know that there is a light at the end of the tunnel,” Sorto said. “Life can be beautiful in a wheelchair. Rancho definitely showed me that.”

“I became a man in this wheelchair and I’m very grateful that I have the opportunity to give back,” Sorto said.